As you probably have seen, we athletes are always trying to find the little things that can help us get that little bit of extra speed. One of the challenges we face is heat, with our bodies trying to get rid of all the heat it is generating, all while the sun is beating down adding even more heat. And on a bike, a helmet especially can get pretty hot. In my quest for glory, I set out to find the coating for the helmet that would keep me coolest, and that led me to what I present here.

I am hardly the first to research this. Materials scientists do research and companies sell products, mainly aiming to keep buildings and vehicles cool, but there are plenty of other applications. But I couldn’t find a clear answer as to what actually works best, so I set out to test a bunch of products, alongside a few more DIY solutions.

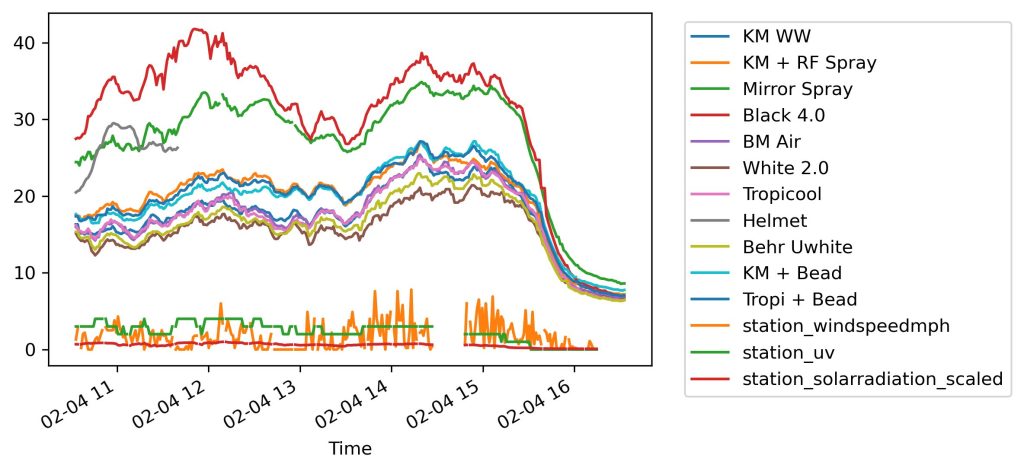

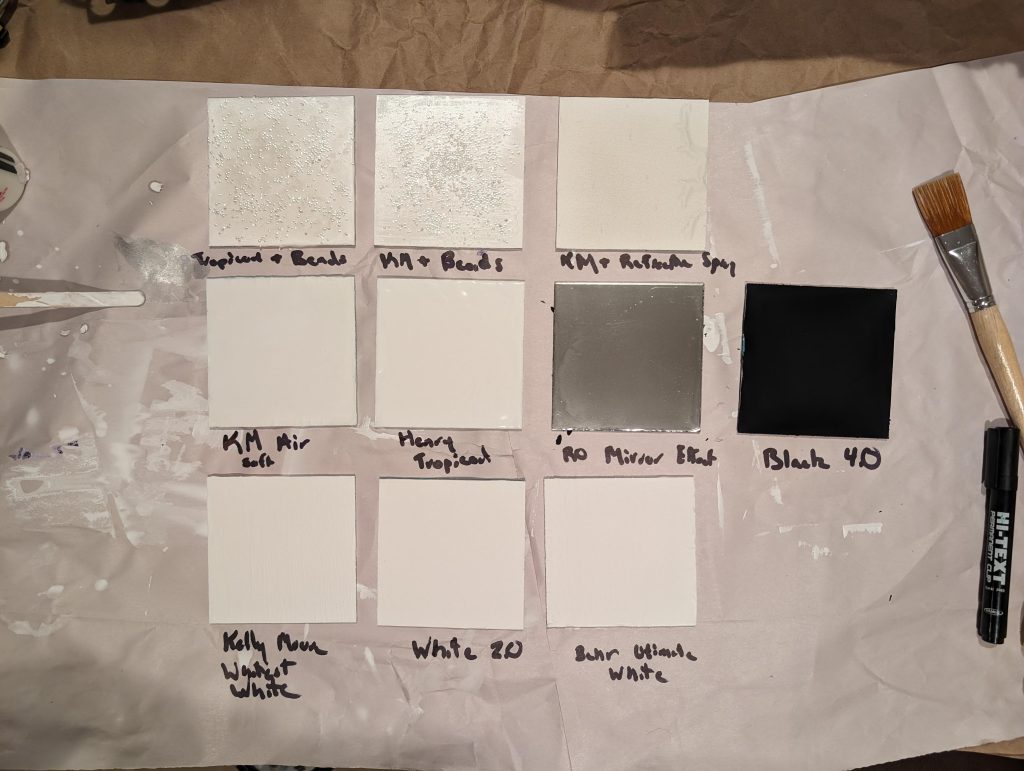

I won’t make you read to the end to find a solution. The answer was pretty clear: simple, pure white paint won as the coolest coating outdoors in the sun. Not cream or off-white paint, very white paint, usually made with a high content of titanium dioxide (~20%) and probably also some silica. Anything with a very high LRV (light reflectance value), or advertised as a “whitest white” or “ultra pure white” was close in my real-world testing, to within a degree or two.

And it definitely is worth running around with a can of white paint. Data from one of the most well-cited studies on runners, showed that the fastest speeds occurred with an air temperature at 3.8° C (39° F) and that going five degrees higher, from 18.8° C to 23.8° C (65° F to 75 °F), saw a 3.7% speed loss. That 5° C is the difference between a light tan and a white paint, and the black, well, that’s the difference between speed and going to the hospital with heat stroke.

Of course, I wasn’t satisfied with the simple answer of using white, which I pretty much already knew coming into this testing. I wanted to find every last little bit of extra performance, to know the ultimate, coolest possible material. Well, let’s find out…

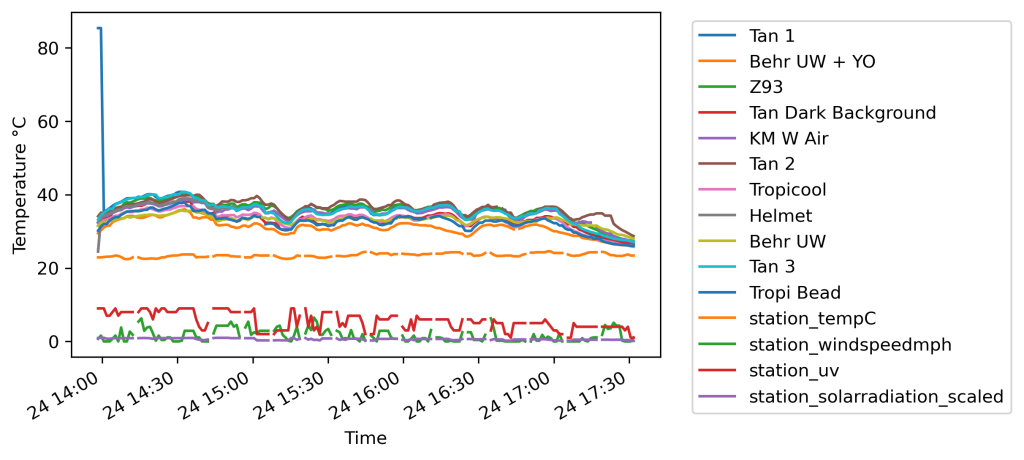

How and Why

You might be wondering, why didn’t a metallic or mirror-like coating do better than white? Shouldn’t that be very reflective? The answer also has a lot to do with the interesting behavior of the comparison black I used, a “blackest black” known as “Black 4.0”. As expected, this got very warm in the sun. But when the sun went away, this sample was also the best at cooling off, cooling off far faster than the white paints, and beating them in returning to ambient temperature despite having picked up much more heat. And to my disappointment, my expected favorite, an expensive Tropicool white silicone roof coating designed for cooling, was decent but not as good as the whitest paints. To understand this, and explore a few potential little tricks, we first need a bit of background.

Materials have three ways to respond to energy passing as electromagnetic waves (i.e. light as the sun, or far infrared as thermal heat radiation):

- They can reflect the energy wave away. White is the reflection of all visible light. A color, say blue, is the reflection only of that wavelength range (450 nm).

- They can absorb or emit the energy. Absorption and emission are two sides of the same coin and materials share the same properties for each in what is known as Kirchhoff’s law. Black is the absorption of all visible light.

- They can be neutral to the wave, allowing it to pass unhindered. Clear, glass, is an example of passing visible waves without either reflection or absorption.

For solar energy, reflecting the wavelengths away is what we want to stay cool.

The chemical bonds present in a material are the primary determinant of how a material responds. Pretty much all materials have to have all three properties (reflection/absorption/neutrality) to some different sections of the electromagnetic spectrum and we want to pick a material that does what we want with the wavelengths we care about. Here we care about solar energy, but this is actually the same thing really as designing stealth aircraft, just that is on a different spectrum/size of energy wave, that of radars. When it comes to paints, a pigment such as “titanium dioxide” (generally the whitest white pigment) or “carbon black” (generally the blackest black pigment) are often the primary determinants of this behavior while the paint base will (usually) be mostly neutral to the relevant wavelengths. Note that chemical bonds are a bit flexible, so materials are rarely all-or-nothing on these attributes, they may weakly absorb or reflect, say 5% of the energy, but we are going to mostly ignore that here.

Metals are an interesting example because they, due to their ‘sea of electron” properties, are both very good at reflecting and also very good at absorbing some solar radiation spectrum. This is why a mirror is not the coolest in the sun. While a mirror does reflect quite a lot solar energy, it also absorbs quite a bit of the solar spectrum as well, and a cooler material would have the reflection without any of the absorption. Silver appears to be the best metal for solar reflectivity and relatively less absorption of solar energy, if you can keep it from tarnishing.

Peak wavelengths of the sun are in the range 480-540 nm, the color green (and cyan, blue-green). Plants actually reflect green because it is the “most intense” light and overwhelms their energy harvesting equipment. You might say it can “cause plant cancer” basically (except DNA damage isn’t the factor, since that is UVC 264 nm but rather photosynthesis machinery). Plants growing in shade start to absorb more green because they need that energy, hence why you see your house plants get darker if they get less sun (human skins do the opposite, darken in the sun, for a different reason, basically our bodies try to put up a wall of absorptive (darker) materials in front of the more sensitive components beneath). White is by far the best color, reflecting all visible light, but if you wanted one color that wasn’t white which would be coolest, you should do as a the plants do and go with, light green. For all colors, you want the “light” (tinted) version of them for maximal cool in the sun.

Note this would differ in a different star system, different stars having different outputs of light, in case you were planning interstellar travel.

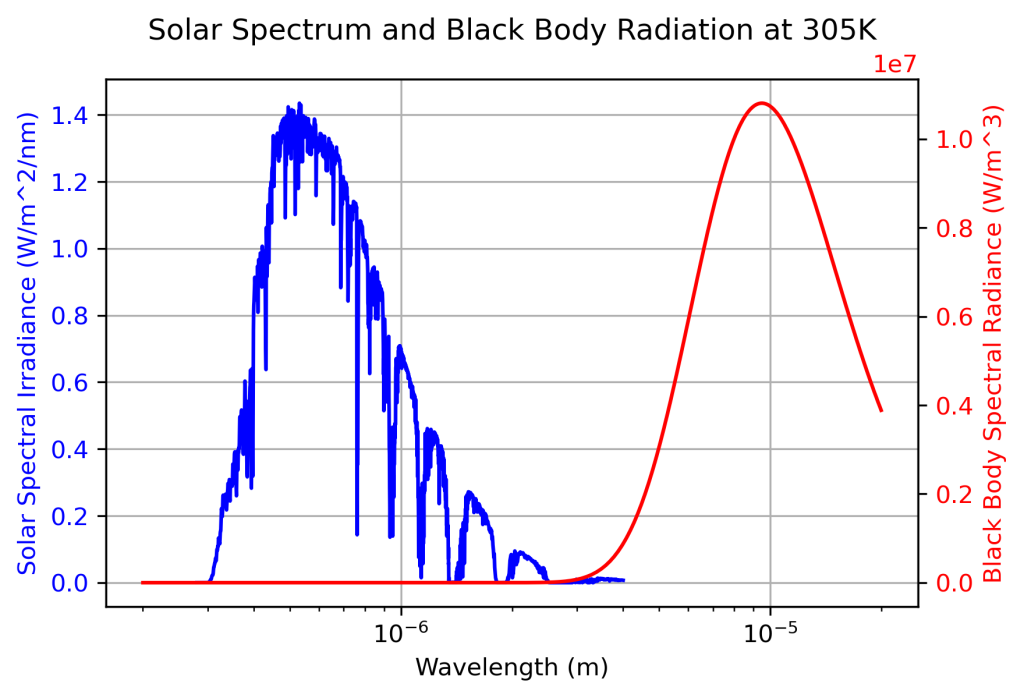

Most of the sun’s energy is visible light, and we humans have excellent built in sensors (called ‘eyes’) that can determine the presence of these wavelengths. Basically, the more white something looks to you in the sun, the better it will be at reflecting solar energy and keeping you cool, and the more black something looks, the hotter it will be under the sun, no more science required. However, when it comes to scientists and other nerds like me battling over making the coolest possible material, they also have to consider the weaker but still strong contributions of ultraviolet (UV) and infrared (IR) light from the sun. We cannot see these, and if they get absorbed they can make an otherwise cool material more hot than it needs to be, and indeed pigments like titanium dioxide do stop reflecting a bit in this range, one of the reasons that even very white objects still get a bit warm in the sun.

Making sense so far? I hope so, because we have to add in another layer of complexity. When it comes to keeping cool, there is another type of radiation we have other consider: thermal radiation. Heat transfers in a number of ways you have probably heard of: conduction, convection, and radiation. Conduction is heat transfer by touch (metal is great at this, hence why it burns you so easily when it is hot). Convection is transfer by the touch of liquid or gas flow (fans and wind are both cooling through this property). Finally, radiation, bodies gain and lose heat through electromagnetic ways called infrared. This infrared light, as emitted by humans and other hot terrestrial objects, is quite a long ways away from the infrared generated by the sun, much longer wavelengths, but generally the same principles apply.

We are mostly going to ignore conduction and convection here. Basically, you add insulation if you want to slow heat transfer between an object and everything else, and you add ventilation or swap in more conductive materials if you want to speed up the transfer. Here we are focused on coatings, which generally won’t have enough thickness to provide insulation, but likely the thickness of some of the roof coatings is intended as a bit of insulation.

Thermal radiation matters because, as observed with the “blackest black” paint, which is highly emissive/absorptive in the infrared range of human body heat (10 micrometers/microns wavelength, “far infrared (IR)”), it can actually accelerate cooling by being a better emitter of infrared than whatever the base object is. Accordingly, if you are indoors, out of the sun, and in an environment where the ambient temperature is cooler than the temperature of the object you want to cool, then the coolest paint is actually… carbon black (10–50 nm particle size) based very black blacks. This Black 4.0 paint was also the most visually stunning of the all the paints tested, it immediately draws your eye, and other paints with a lot of appropriately-sized carbon black would likely look similar.

For another twist, another material that has good infrared emissions at 10 micrometers is silica (SiO₂). Silica, basically sand, is often used as a thickener or filler agent in paints, yet it is also playing an active role in the thermal properties as well. Silicon carbide, rarer, also has similar properties. After learning this, I was unsurprised to find “silica” on the data sheet of all the coolest white paints.

Barium sulfate made the news for a “whitest white” pigment by combining UV and Visible reflection with high thermal emissitivity like silica. It does it all, it would seem. However, it is actually less white than titanium dioxide, and less emissive than silica, so the primary advantage is the UV blocking. It is worth using but is not necessarily the “ultimate” coolest white pigment as can be seen claimed in some places.

Incidentally, this silica is part of the material that helps make a paint “matte” vs glossy. Fillers also can increase reflectivity by providing optimal particle spacing while also making a surface more matte. This means my original hypothesis, that gloss paints would be cooler, is wrong, or at least, more complicated. For reference, gloss is not so much a measure of amount of reflection as the coherence of the angle of reflection. From what I can tell so far, the coolest whites are probably going to be ultra pure whites with a “satin” or “semi-gloss” finish, rather than a very matte or very glossy finish. In sunlight, they should appear “brightest” rather that “most glossy.”

Engineering this would be an entire field of chemistry to dive into. The size of the particles and if they are coated or treated in some way, can also have a large impact on the properties of the pigments we have discussed, as can binder-pigment interactions.

Particle size of the pigment seems to be the most important of these properties. Generally for scattering, particle size should be half of the wavelength you want to scatter (for solar energy, a mix from 150 nm to 500 nm, with 250 nm as the peak, if you could only pick one size). For absorption, generally smaller is better. However, there are a number of rules (Raleigh scattering, Mie Scattering) but a vague rule seems to be that around a fifth the wavelength or less is fairly close to maximum absorption. Note that particle size alone will not make a material reflect or absorb that wavelength. It’s the combination of chemical properties of the material as well as the size of the particles. Particle size and other particle treatments is a large part of the “secret sauce” of chemists here. Many companies publish their paint compositions in data sheets, but not, you’ll notice, the particle size they use.

For example: in application, a 2-5 micrometer size looks like a target for carbon black that would emit human temperatures (far IR) quite well but be less absorptive of solar radiation than pigment grade (smaller particle) carbon black. This carbon black would still absorb plenty of solar energy, probably looking more like a gray, but not nearly as much as a pigment grade carbon black. This would be my choice for a “coolest” coating for indoor use where rare but occasional dappled sunlight might be expected (keep in mind that convection cooling, i.e. fans, are much more powerful cooling systems than radiation, but can be combined, i.e. carbon black on top of cooling fins).

For reflectivity, the refractive index of the medium (the base goo) for the paint also impacts reflectiveness. Lower is better. Fancy engineered paints use various ways of trying to get air into the mix, as air is the least refractive, but a simpler approach I tried was using beeswax-based paint medium, although I had issues with it cracking in the pigment load I used. Beeswax is slightly less refractive than acrylics and other common media, but realistically acrylic is the most practical general medium here.

There’s far more that can be explored. Some materials, for example, if applied in incredibly thin layers (‘nano coatings’) can be transparent to light. Silver has this property, and can be used in window coatings to reflect IR and be seen through clearly, even though a thick layer of silver is obviously not translucent (although it is quite shiny).

The biggest challenge I see is that, while you can, with moderate ease, highly engineer a material for great performance in one set of conditions (stay cool or stay warm in the sun), most things we use we expect to work in both conditions, to be both cool in summer and warm in winter. There is a possible solution here generally termed “thermochromic” pigments. These change color in different temperatures, so they can be white when it is hot and dark when it is cold.

These are pretty exciting but also have a few challenges. The biggest challenge I have noticed with thermochromics is that the available temperature change points are often not where they would be most useful. Another challenge is that they aren’t as black and white on the transitions as would be ideal, going from mostly white to a dull gray, for example, and being blotchy in warm vs cool areas of a surface. Their poorer ascetics is one of the reasons these haven’t been adapted, say, for car paints, even though they would probably be appreciated in places like where I live, with cold winters and rather hot parts of the summer.

My only real personal innovation here that seems to add a small breakthrough is the use of yttrium-oxide-based invisible orange glow-in-the-dark powder. This is based on NASA research that uses yttrium oxide as a pigment (it is a good thermal emitter apparently). The twist is that I used a “doped” version that makes it a glow-in-the-dark pigment. This pigment takes UV light and converts it to visible light. My theory is that this can absorb UV light (which neither titanium dioxide nor barium sulfate fully reflect) and convert it into a visible light which can be reflected by those white pigments, and thus used on the outermost paint coats with pure white layers underneath.

I only had one tile with this glowing yttrium oxide mixed into some Behr Premium Ultra Pure White (semi-gloss), but it was the best in some runs (but not on all runs). Even if it did succeed, I am not entirely sure if the yttrium oxide itself or the ‘doped’ version to make it UV-to-orange is what drove the improved cooling, or both. Regardless, if all the buildings of the future glow faintly orange at night, you have me to thank.

To that same end, it seems reasonable to conclude that a properly fluorescent green may be slightly cooler than a regular green, making it the coolest single color.

All of that said, if you wish to attempt a custom “coolest” white, here are some starting formulas that should produce decent results. Neither of these is “perfected” but they should be reasonable starting points. I don’t think there is any real need to do this as there are plenty of excellent commercial whites. The main advantage here would be that you have control of the full process to assure the right pigment sizes, and so on, are used. Get a couple different paints and see what looks brightest in the sun to you.

DIY Coolest White Recipe

- 15-20% titanium dioxide (~250 nm particle size, “pigment grade”)

- 5-10% barium sulfate (< 1 micron, pigment grade, reflects UV, thermally emissive, and filler, optional)

- 5-10% silica (~1-5 µm particle size, thermal emissive and filler) 50% medium (acrylic-, wax-based, etc., generally aim for low refractive index)

- Yttrium oxide invisible orange glow-in-the-dark powder, optional, outermost paint coats only

Another option would be split the properties into different layers. Multiple layers of different materials is how most fancy thermal coatings like those for premium windows work. Order matters. For this, layer 2 must have enough coats to completely hide layer 1.

- Layer 1 (bottom): Blackest Black Carbon Black (for thermal emissions)

- I used Black 4.0, but this should be easy enough to reproduce. Try to get the smallest-sized carbon black (something like 50 nm particle size) and mix with a base medium until it looks like you are staring into the void.

- Layer 2 (outward): Whitest White Paint

- 12% titanium dioxide (250 nm particle size or use a mix of particle sizes from 100 nm to 600 nm)

- 2% filler (small, i.e. 1 micron or less ideally, i.e. silica or pigment grade barium sulfate, optional)

- 86% medium (low refractive index, transparent to far IR)

- Yttrium oxide invisible orange glow-in-the-dark powder, optional, outermost paint coats only

I also added a few drops of tinuvin (HAL UV stabilizer) to my custom mixes to try and make sure they had more durability with long exposure. That should not impact cooling, however.

You can try adding the glowing yttrium oxide or even just a bit more pigment-sized titanium dioxide to an existing commercial white paint as well. Note that there is actually a point of no return with adding more titanium dioxide, and the premium whitest whites will probably be close to that point, so not worth adding more. However cheaper whites often skimp on titanium dioxide as it is a more expensive ingredient. Adding too much extra pigment will often ruin the paint, make it crumbly by messing up the pigment to binder ratio too much, so try some samples with small amounts and see what you can get away with.

Avoid titanium dioxide, or indeed any pigment, sold for cosmetic, skin care product use, the particle size is usually too small.

A third option would be to recreate Z93, a coating used on the International Space Station. I found a document showing it is made in a 4.3 to 1 ratio of zinc oxide and potassium silicate, with water as needed. However, my test batch of this was rather crumbly, an issue I did not resolve.

As a final bonus, silicon carbide in moissanite form is theoretically even slightly better than titanium dioxide as a reflector. It is also a good far IR emitter. It is theoretically the best pigment, that no one has used due to sourcing difficulties, but lab made moissanite production has grown. I have always wondered if fine moissanite powder could be sourced from gemstone cutting and used as a pigment. Grinding this very hard material and sorting into ~250 nm powder would be difficult.

Conclusion

In general, if the sun is around, solar energy management plays an important role in heat management. Bright white is coolest, darkest black is most hot. Here we studied paints but the same pattern would be true with fabrics and any other material.

Managing the far infrared of thermal radiation is generally a bit harder to do than managing the solar energy, as there are more complex options for materials, and judging their quality is not as simple as seeing white or black. Convection cooling (air flow) is more important for most cooling. Many, but not all, visible blacks such as carbon black are also very thermally emissive, along with some materials like silica and barium sulfate.

For most outdoor sports like cycling, a bright white-painted helmet can help keep cool, enough to noticeably improve performance. But there are some other cases where this isn’t true. Going for the hour record, indoors, no sun, in a velodrome, carbon black would actually be better for cooling. In racing in the desert on a hot day, where temperatures are above body temperature, far IR absorptive/emissive materials (like silica) should be avoided in the white paint, but in most events IR absorptive/emissive materials will actually be cooler. For racing on a very cold but sunny day in winter, a solar absorptive but far IR reflective or at least translucent material (metal foils, paints with metal particles (mirror effect), metallized films more commonly, or research solar selective absorbers for state of the art) would be the right choice.

Chemistry has largely solved the challenges of managing pigmentation for proper solar and thermal management, although it is still complicated. Further developments are expected, but generally current materials are near maximal possible performance. What still hopefully will see both further development and affordability are thermochromic or advanced phase-changing materials that can shift for different conditions (i.e. winter vs. summer) for better year-round performance.

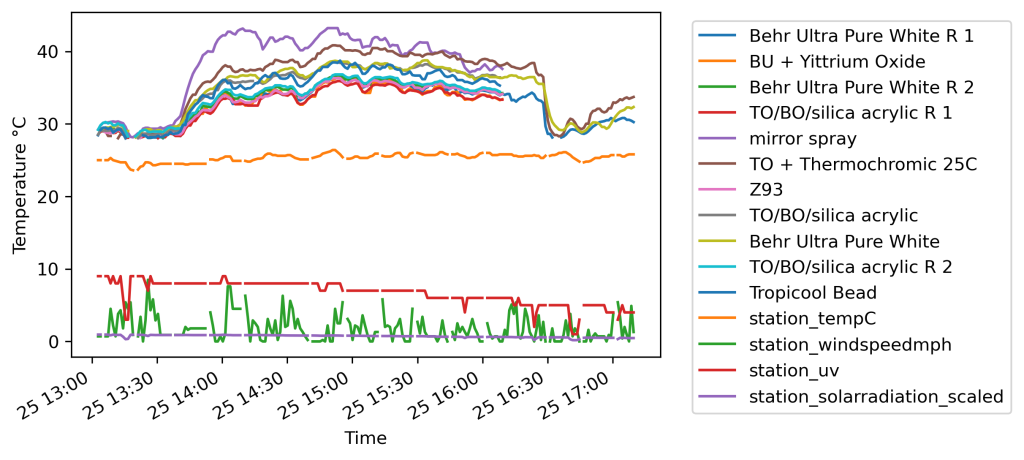

Testing

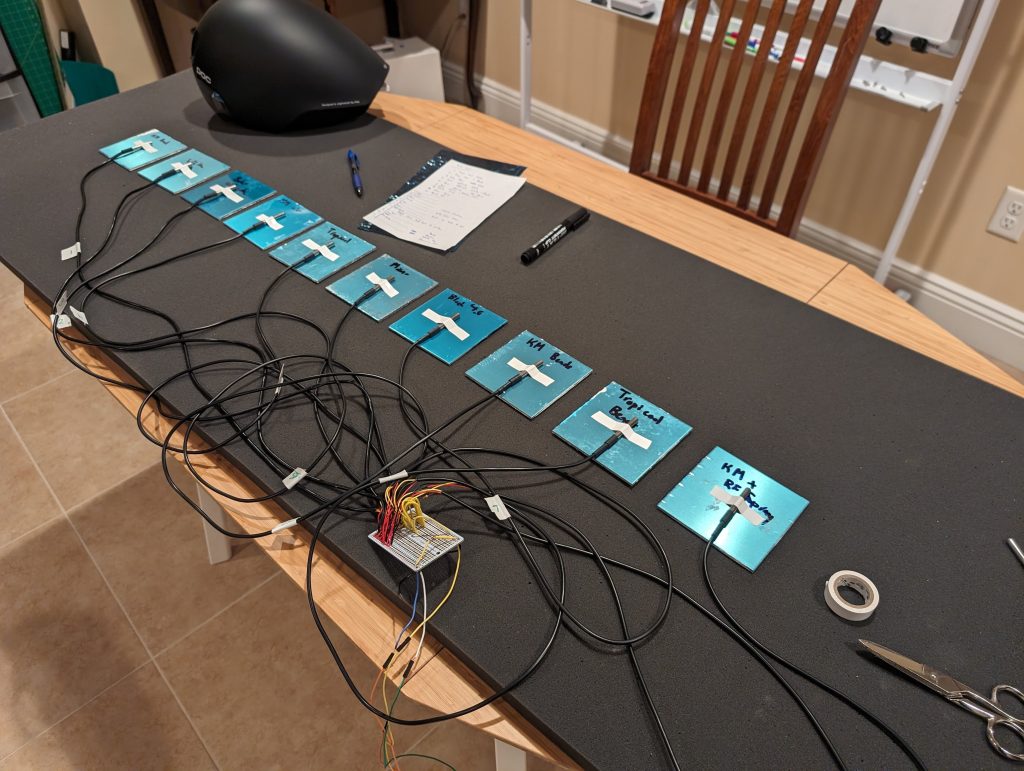

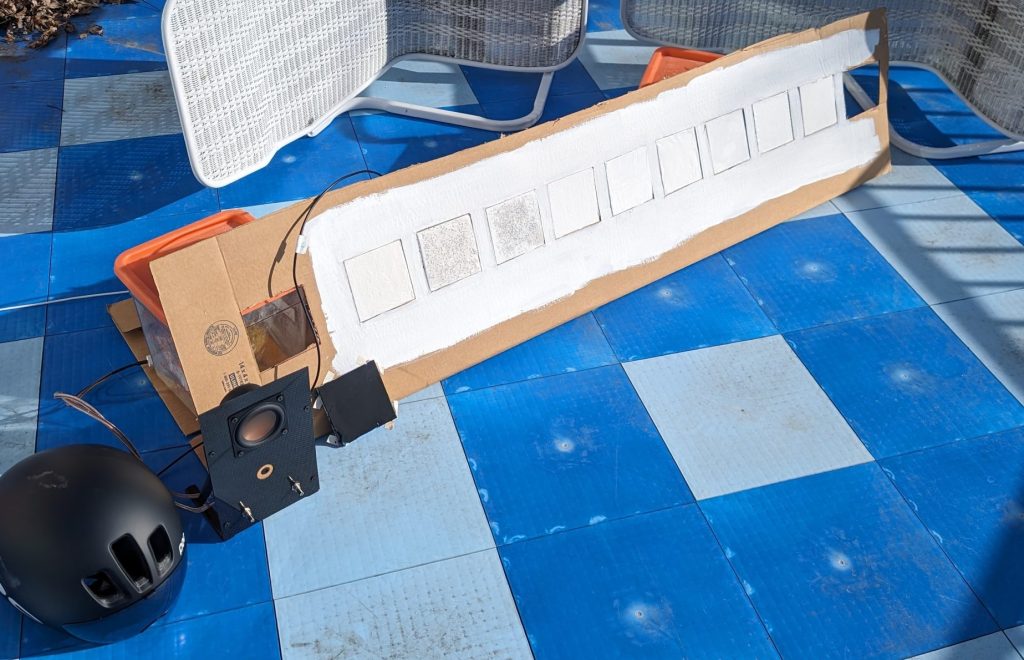

For my testing here, what I did was take10 four-inch aluminum tiles and placed them evenly spaced on white-painted cardboard. Each tile was painted with several coats of the test coating. Behind each of these tiles I placed a DS18B20 one-wire temperature sensor and recorded all of these probes on a Raspberry Pi. I also pulled air temperature and solar intensity data from my backyard weather station over its API. I used a set of thermal binoculars to monitor the tiles and check for uneven heating of the base board. Testing occurred in February, March, and July 2024.

These temperature sensors aren’t particularly accurate, listed as plus/minus half a degree. Precision didn’t appear to be the greatest either. In a mixed water bath test where they should have had the same readings, there were some differences. I added a small offset from this calibration to try and align the values. One probe was worse than the others and not used for important measurements, there being 12 connected probes. This level of accuracy, while not great, is probably sufficient, one or two degrees warmer not being enough of a difference to matter much in most real world use cases.

I discovered a number of things along the way:

- Any wind makes a substantial difference. Tiles at the end, even in light wind, were cooling faster. Care needs to be taken to standardize air flow.

- My attempt to test 10 different paints at once, each with only one sample, didn’t give enough accuracy for the similar whites as there are subtle variations in each position in the test grid and each probe. To really figure out the best, at least three samples of three paints, alternating along the length of the test board, and averaging the results is needed.,

I tested a number of things that I haven’t really discussed above. I tried retroreflective beads (as used for highway paint). These increased the warming of the surface. I tried mirror spray (aluminum flakes) and this became very warm. The roof coating was fine, (though to me a disappointment), but as I have discussed above may have had other features (like a bit of insulating depth or better durability).

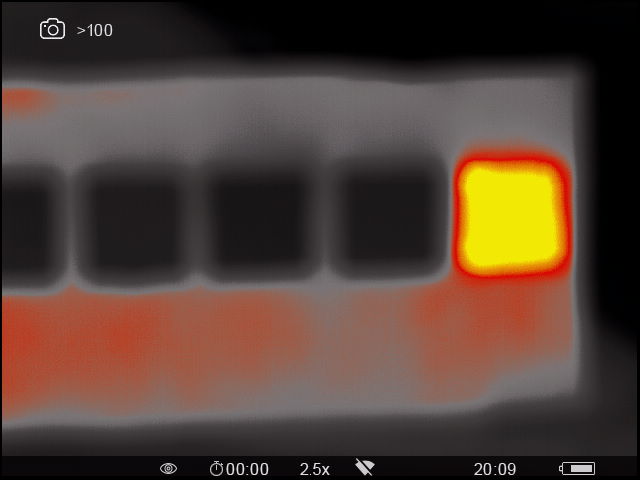

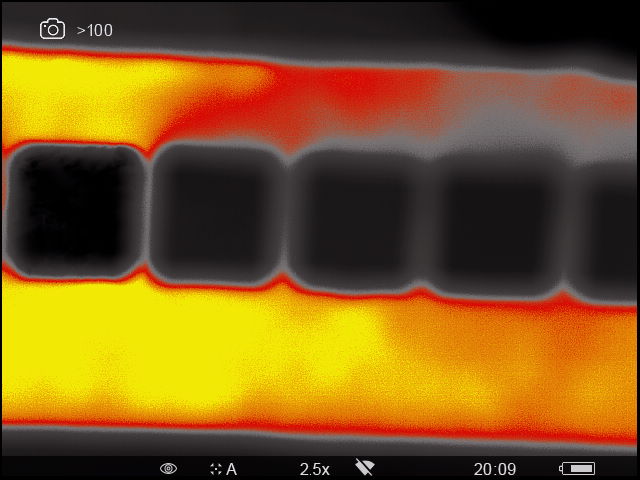

Noticeably all the white tiles helped cool the area around them. For many of the tests I ran an empty spot in the middle and the cardboard around this was warmer than around the white tiles, as observed on thermal imaging. Tests could be slightly influenced by their neighbors in that a hotter tile could be cooled a bit if two of its neighbors were among the coolest, and in turn it could also heat them up. Spacing was wide enough and the material low enough conductivity this should not be a major issue, but thermal imaging suggests the “warmth fields” did overlap a bit.

That thermal imager wasn’t precise enough (not radiometric, for field use) to measure the temperatures but was helpful in validating the setup, and a radiometric one could probably be used instead of the temperature probes as a form of monitoring, although you’d lose the live multiple-hour data streams I captured here.

I hand brushed on all of the tiles except one which was airbrushed, and the mirror effect spray which was sprayed. I had been thinking that how the paint was applied could impact results, however most of these had enough flow that they were pretty smooth, self-leveling on the smooth tiles. Thickness of the coatings actually looked to matter more. The tiles had a blue plastic backing that helped, as all tiles were given coats until blue was no longer visible.

Incidentally the silicone roof coating picked up a ton of hair and dust, while the paints stayed pretty clear, over the course of several months inside. The roof coating, however, did hold the retroreflective beads best, although they weren’t useful for cooling in the end.

A number of runs have “helmet” in the results. This was the temperature probe taped inside my bike helmet for reference. It wasn’t entirely consistent with the tile lineup, because for one, it had ventilation holes and insulated walls, but generally appeared to be among the hottest when properly tested, a bit less than the blacks (it was painted gray from the factory).

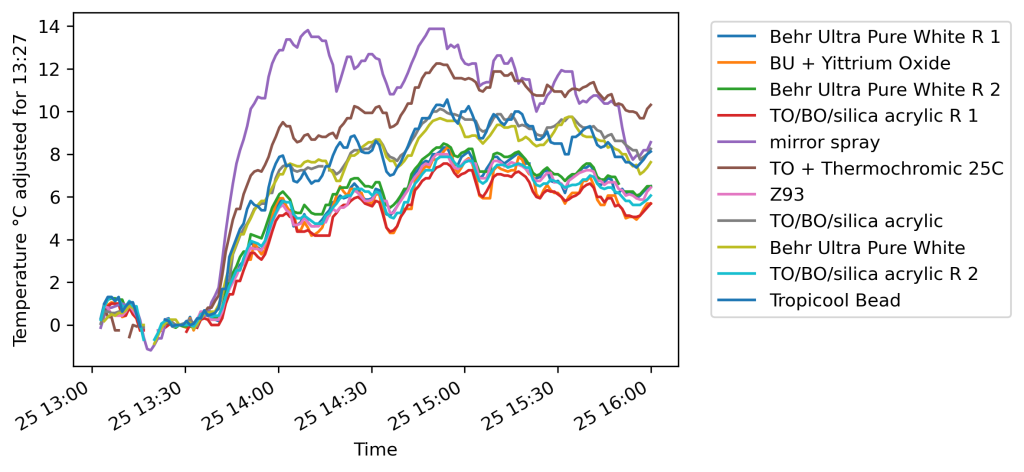

On a small handful of tests you can see R 1 and R 2. These were tiles that were paired for one to one comparisons next to each other for improved consistency.

I am not particularly happy with the consistency of my results. While there are a lot general trends that seem to match the theory nicely, and I think most runs are reliable, I have one run, for example, where Tropicool with retroreflective beads (normally one of the worst), managed to slide into second place for coolest. Not consistent. I am fairly certain there is some variability in the temperature probes. I would not use DS18B20 probes again for repeating this, but something more accurate. I also observed in thermal imaging that ends with more airflow had more cooling on the cardboard, and likely the tiles are off. I will note that, if you dive into the raw data, there are a few cases where shade moved across the board, progressively covering tiles, but that was easy to account for.

One small correction I did attempt, was to adjust all tiles by an offset for when they all briefly had been in the shade for a while (due to passing clouds). This could theoretically be the main source of error in probe variations, as could a “cold start” for calibration out of the sun.

Overall, I did enough different runs on enough different setups of probes and tile positions to come to a very clear conclusion that very pure whites were the coolest. I was not able to be sure if something like White 2.0 was actually any better than Behr Ultra Pure White–that falls beyond the precision capabilities of my setup. There is some evidence that my homemade acrylic with pigments slightly outperformed the Behr paint, and I think the evidence is certainly clear that a DIY mix can at least go toe-to-toe with the best commercial paints in cooling capability.

Yttrium oxide orange glow-in-the-dark powder, my most successful of various experiments, had multiple runs where it was the best on raw or best on adjusted data, but also some runs where it was not. I would mark this as a “very promising result in need of further testing.”

I did not test, but wish I had, more layers, ensembles if you will. My main goal had been to find just one paint that alone would be best. Yttrium oxide “glow” was the only one where I had another, different paint layer (a pure white base layer with no yttrium oxide to make sure orange was reflected out from the glow layers). I would really like to test a whitest white on top of a blackest carbon black for comparison, as I believe that is another very promising combination.

Assorted References

NASA does a bunch of research on this type of thing for cooling systems in space, and much of that is published in the public domain.

https://coolroofs.org/directory/roof?orderBy=aged_SRI&sort=desc

https://webb.nasa.gov/content/observatory/sunshield.html

https://sos.noaa.gov/catalog/datasets/climatebits-solar-radiation/

https://tfaws.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/TFAWS2020-CT-103-Wilhite-Paper.pdf

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19990021250/downloads/19990021250.pdf

https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA297745 (4.3:1 pigment to binder ratio)

240694

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Solar-reflectance-and-emissivity-of-paints_tbl5_281753779

https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2023/va/d3va00161j

https://www.science.org/content/article/cooling-paint-drops-temperature-any-surface

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-barium-sulfate-can-replace-titanium-dioxide-sookie-b

https://aviantechnologies.com/2019/01/22/i-need-it-white-what-do-i-do/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_refractive_indices

https://www.flir.com/discover/rd-science/use-low-cost-materials-to-increase-target-emissivity/

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/phpp.12214 (particle size of TiO2)

https://coatings.specialchem.com/selection-guide/titanium-dioxide (really good)

https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C13463677&Type=IR-SPEC&Index=0

https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=B6004658&Mask=80

https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C7631869&Type=IR-SPEC&Index=4

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Titanium_dioxide_nanoparticle

Code and Files: https://github.com/winedarksea/coolest_paint

Colin Catlin, 2024